I wrote about my crazy up and down life on an earlier post, and I happened to be a high school English teacher during those tumultuous years. I used the classroom as my opportunity to explore all I could about WHAT THE HECK WAS HAPPENING TO ME! I was looking for foundational truths during this period: What is wealth, really? Why do I want it? Do we need it? What does money solve and what can it never solve?

They say that A.W Tozer read both the Scriptures and Shakespeare on his knees. He claimed that he read the Scriptures to know the heart of God and he read Shakespeare to know the hearts of men. In fiction we find the vast terrain of our humanity — the extreme: the valleys and heights, the deserts and the lush gardens of our the human soul. We can glean from stories and characters the truths of our limitations and tips to a life of wisdom. I believe that. I taught that. They call it “the humanities” for a reason, for there are clues about this strange human experience in literature if we look for them. Read more, not less.

Most teachers can’t pull this off because they don’t have freedom over their classroom. I enjoyed the last bit of instructional autonomy afforded to anyone in the public school system. I completely governed my own curriculum–a thrill for a teacher. I assigned the papers and the readings I wanted to assign. I was left completely untethered/unrestricted because my students knocked the top out of state exams. Reading excellent literature and forcing students to write more (NOT less) critical evaluation is a great recipe for test prep – imagine that. What used to be common sense is now so radical!

I entered the teaching profession because I had the financial backing to pursue whatever employment I desired. Investing in young people, equipping and exhorting colleagues, and building a culture in my classroom that hummed with the Kingdom of God light was my total aim: I wanted a classroom that modeled righteousness, peace, and joy (Romans 14:17). For seven years, I believed the Kingdom pulsed out of room 312. I certainly made every effort to cultivate that culture. There were many prayers in that room: with faculty and students. There were a few moments of personal/desperate prayers as well — bone shaking prayers of personal need.

In my classroom, I always assigned F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. I taught them out of a selfish desire to understand— if you haven’t read them, you really should. They are fantastic! For those unaccustomed to modern American Lit – I will give you a couple of guiding touchpoints on each. No assignments/no quizzes. Don’t worry; I am reformed!

- The Great Gatsby is the story of the lust for wealth and prestige (in the Roaring 1920’s) set in a very decadent Long Island, NY…

- The Grapes of Wrath is the tale of grinding poverty and sacrifice among the poor languishing in rootless hunger in the 1930’s…

- Death of a Salesman is a play about a middle-class salesman in the 1940’s who lives under constant pressure to succeed and not slip again back into the lower class.

You will notice that this sequence spans three consecutive decades and examines wealth, poverty, and middle-class of American life–and are some of our culture’s most lasting meditations on the subject. These characters are tortured in their own ways and through the titles we find that the American Dream, for all it’s claims and promises, may be just that! (I threw in Biggie Smalls Mo Money, Mo Problems and other poems and short stories to spice up the all-white-all-male novels, of course…)

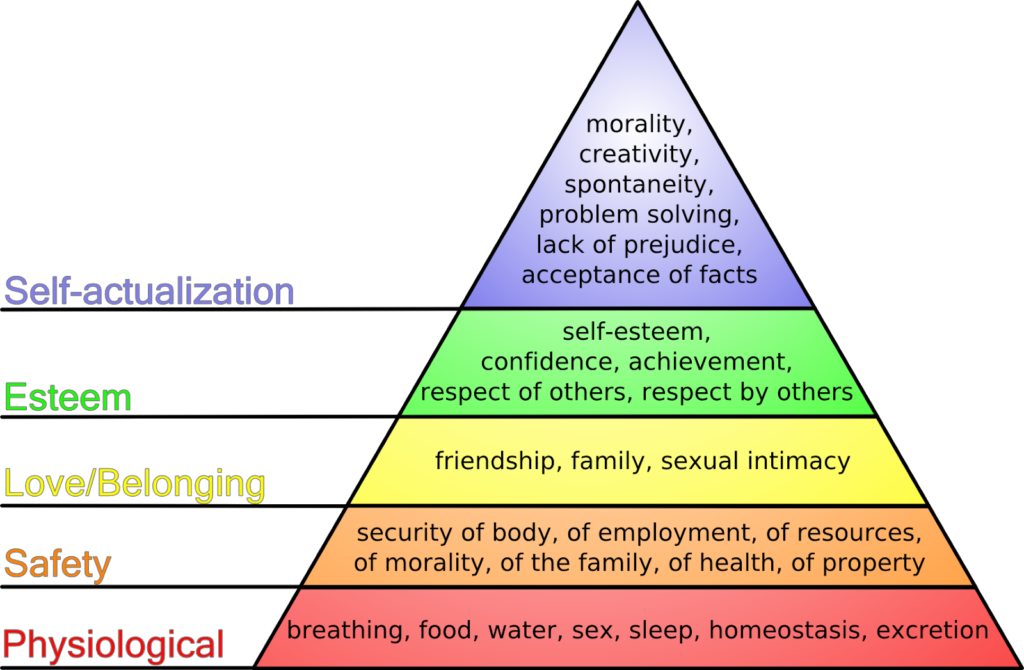

But, I didn’t just jump into these big titles; I always framed our readings in terms of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. You remember that multi-color triangle from your intro to Psychology class, right? Here’s the famous image right here:

(My students always loved that bottom right term: excretion. Hilarious!)

We talked about each work’s protagonist and where they were on the triangle: what motivated them, what fear terrorized them, and what they dreamed about. Those poor Okies in The Grapes of Wrath were at the bottom — they’d run after a rabbit by the roadside to meet that physiological stomach need, but they had more capital toward that top portion of the triangle than any of the other characters we examine. They were creative problem solvers, respected others in poverty, and kept tight family bonds. Jay Gatsby lived among the elites, but he had no core: he had middle-pyramid needs that jeopardized everything. Raised poor, he mimicked the aristocrats and deceived to win their love. Fitzgerald would later write:

“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are. They are different.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald

There is quite a bit in that quote, but we should save that for another stellar Abraham’s Wallet article.

Finally, we looked at poor, pitiful Willy Loman (the Salesman) who never got much of that Maslow orange band because he wanted to be a big shot in his own mind – and everyone suffered around him as a result. Even worse, he built insecurity into the rest of his family. These novels were tragedy tales surrounding our human wants/needs. We always landed with a core question: what matters most? Man, we had great conversations!

It should be clear how the English course overlaps with my own story, and here at Abraham’s Wallet, we’re constantly evaluating the placement of dollars, short-term vs. long-term allocation of resources, and the wise use of debt versus stupid consumer debt. Those prosaic lessons in filthy lucre are framed, correctly, as faithful stewardship toward expanding our households, communities, and the Kingdom of God. As this site is repeatedly expounding, there is crazy complexity as these two forces dance together: eternity and money. We–you and I–are the decision makers attempting to waltz well.

For those who always just wanted the Cliff’s Notes and swapped cheat-sheets in the hallways – I’ll leave you with a quick take away. Here is one truth found in each of the titles above. Please feel free to disagree with me in the comment section below — I love the push-back banter! Most educators do.

The Tom Joads of Steinbeck’s world were perfectly willing to part with what little money they had when they encountered others in need. Their own hunger and despair furnished their family with soft hearts for others — their own need taught them to take great pleasure in the simple blessing of a hot biscuit, or give their last drops over to those in pain. I’ll spare you the spoiler ending, but the last chapter is profound on this point. Sadly, their lowly culture hated those with wealth. They distrusted all institutions because of that poverty mentality; they were badly treated and their multi-generational resentment propelled them further into poverty. Their generosity is to be mimicked, even while their resentment breeds destruction.

The Willy Loman of Miller’s world missed the richness of his family life and never relished his daily bread because he panted for the recognition and honor he knew the world attached to financial prosperity. Never content, he ached for more and drove his sons from him as he pushed them to reach height he never attained. He preached success and moral excellence but was a hypocritical failure by his own standards and he suffered suicidal torment as a result.

The Jay Gatsby of Fitzgerald’s world made a Faustian deal with the devil to temporarily lead the high life in an effort to win Daisy. He exchanged real success for the ephemeral charade of success. A modern Gatsby would have leased a Mercedes S class and taken out jumbo loans to convince others he belonged in the best zip code. Fitzgerald treats the elite class like Steinbeck did — those with wealthy are most likely A-holes who should be knocked down a few pegs. Surely, we know wealth is a blessing and that it can accomplish much in this world. None of these writers acknowledge this truth; none of these writers knew much of our grand-dad Abraham. In that way, I suppose Moses wrote a better wealthy character than the 20th century literary luminaries!

Oh – and what about Maslow’s pyramid?

A final thought: I would conclude by reminding us all that Maslow’s Hierarchy is a scale of our human need, and we all have those needs. The premise of the model is that you can’t address top line needs until those nearer the base are met. Shockingly, in the LORD we have everything from daily bread and clothing (Matthew 6) up through identity, community, and wisdom. The disciple in submission finds that every need is met in our Provider and Protector – we are most self-actualized when we are aligned to His purposes in our lives and on the earth. When we sit navel gazing or lamenting that the winds of fate have treated us harshly, our eyes have fallen to the wrong place. I can say with the Psalmist “all of my springs are in you” no matter what I drive, no matter what my stock portfolio says, and no matter how shiny my shoes may be. And — you can say the same thing.